Kerkrade history in a nutshell

The place name "Kerkrade" dates back to the Middle Ages. The suffix "rade" refers to the verb "rooien": to cut down and cultivate woody areas. You can read more about the history of the municipality below.

The Land of Red

Around 1000, Kerkrade, Kloosterrade and 's -Hertogenrade came into existence close to each other as a result of clearing heath and forest areas. The parish church was in Kerkrade and most of the people lived there.

Kloosterrade was - the name says it all - an abbey and 's-Hertogenrade was a small settlement with a high castle owned by the dukes of Limburg. Kloosterrade grew into today's monumental monastic complex Rolduc, which celebrated its 900th anniversary in 2004. The "Annales Rodenses," the chronicles of Rolduc from the twelfth century, are among the oldest written historical sources in our country. The market town of 's Hertogenrade had city rights in the Middle Ages and also the right to mint its own currency. In its heyday, the Land of Rode, which was governed from here, included an area as far as Vaals.

The Treaty of Aachen

In 1789, a hungry mob stormed the prison in Paris and Europe went adrift. French troops conquered large parts of the Southern Netherlands in 1794, putting an end to medieval authority. The Land of Red was incorporated into the French empire and when Napoleon finally found his Waterloo in 1815, diplomats in Vienna drew new European borders on the maps "off the cuff." The exact border between the kingdoms of the Netherlands and Prussia was established by the border treaty of Aachen in 1816. Kerkrade and Herzogenrath were separated not because this was the explicit wish of the local population, but because a large commercial road (Nieuwstraat) and a small river (De Worm) from Vienna seemed a "natural" boundary.

Nieuwstraat and all the Kerkrade area east of it became German, in order to prevent part of the important trade route between Aachen and Geilenkirchen from encroaching on Dutch territory. The only one that did not have to care about this state border was the Domaniale Mine. Although it was located on the Dutch side of the Nieuwstraat, it was allowed to continue to use its entire concession field, of which about 130 hectares were now on German territory, undisturbed.

Boundless

The state borders only became tangible in practice around World War I when an iron curtain was erected on Nieuwstraat with a height of about two meters to hinder espionage, desertion from the German army and smuggling. As international relations improved after World War II, the border fence on Nieuwstraat/Neustrasse became lower and lower: the initially meter-high wire fence,which split the street into a Dutch

and German parts, was even replaced in1968 by leicon blocks only 40 centimeters high.

A major reconstruction of this road began in 1993, and by now the border has even become invisible: in the streetscape of Nieuwstraat, one can no longer tell where Germany begins and the Netherlands ends. Today, in an international context, Herzogenrath and Kerkrade are once again cooperating fraternally under the name "Eurode".

From black to green

Kerkrade was the oldest mining town in the Netherlands. Coal was being mined here as early as the Middle Ages. Starting in the 17th century, Kloosterrade Abbey put expertise and money into more professional coal mining. The mining industry grew into the region's most important employer in the 19th century. Kerkrade's location, in a remote corner of the Netherlands, caused the municipality to orient itself economically mainly to the German hinterland. This was compounded by the poor infrastructure. For example, it was not until 1949 that the center of Kerkrade became accessible by rail via the "miljoenenlijntje" passenger railway. The "miljoenenlijntje" owed its name to the exceptionally high construction costs for that time, caused by the many hills and valleys that had to be "overcome" during the construction of the route. Today, the line is operated by the South Limburg Steam Railway Foundation (De Miljoenenlijn)and has become an important tourist attraction.

In the early 20th century, Kerkrade was the most important place in the eastern mining region. In Limburg, only Maastricht, Roermond and Venlo were larger. More than half of Kerkrade's labor force was already working in the mines by 1900. Well into the 1960s, Kerkrade remained economically dependent on one industry: the mining industry. When the mines closed their gates, the curtain also fell for many supply companies in the industrial sector and for many service companies, and Kerkrade was actually faced with high unemployment for the first time and growth came to an end. By now, however, very little in Kerkrade recalls its "black" past.

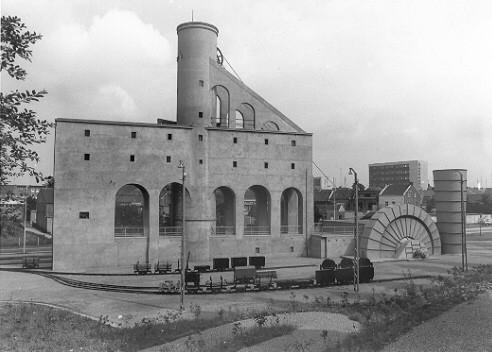

Since 1957, "d'r Joep," a statue in honor of the unyielding miner, has stood on the Markt . Mine shaft Nulland has been an annex of the Discovery Center Continium, Museumplein Limburg, since 2006. Former cowhands of the Domaniale Mine established the foundation "Cowhands of the Domaniale. They refurbished the shaft and furnished it as a museum. Here they have been providing tours for various groups, from elementary school classes to families and from associations to company outings, since 2013. In addition, Schacht Nulland has been a wedding location (for up to 25 people) since January 1, 2015. In the shaft you can admire an original elevator, a mine bicycle, coal wagons, various machines and all kinds of objects and photos from the mining era. Recently, visitors can also take a look at the upper floor.